Late in 2013, long-running news magazine Dateline NBC launched an online contest called “Don’t Watch Alone.” Viewers were asked to make a case as to why correspondent Josh Mankiewicz should drop by and watch the program’s 22nd season premiere—a story of an adulterous wife who spikes her husband’s Snapple with antifreeze—in their home. This followed a similar contest the previous year, where viewers were urged to tweet photos of themselves watching an episode of Dateline alongside a paper cutout of Mankiewicz. In the case of “Don’t Watch Alone,” a group of friends from Stamford, Connecticut, won the honor of the journalist’s company. As an added bonus, fellow Dateline correspondent Keith Morrison—the Hutch to Mankiewicz’s Starsky—showed up unannounced. The winning viewers were ecstatic, as if their favorite television characters (Starsky and Hutch, let’s say) had magically materialized in their own living room, ready to hang out, shoot the shit, and watch some TV.

[Begin Dateline voiceover.] So what was going on here? Were these contests some sort of sick joke? Watching a “true-crime” TV show with the stars of that show? Posing with paper cutouts? Dateline? Clearly, these contests were nothing more than cheap publicity stunts from a disreputable tabloid news magazine desperate to remain relevant, desperate to hook undiscriminating viewers who had nothing better to do, contests that were just as trashy and lurid as the dime-store “murder-of-the-week” stories it so often profiled…

Or were they? [End Dateline voiceover.]

Yes, for an alarming number of Americans—myself included—Dateline has become appointment viewing. Mad Men, Downton Abbey, and the ilk are fine, but there’s a distinct, guilty pleasure in staying home on a Friday night, dimming the lights, sounding off on Twitter with other likeminded fans, and watching the sordid true-life tales of murderous spouses (usually husbands), sorrowful family members (usually parents), and sinister motives (almost always infidelity) unspool over the course of an hour, all narrated by the stern and sonorous Morrison, or the rumpled and incredulous Mankiewicz. Murder, shattered families, and desperate cries for justice: perfect for a cozy night of popcorn, wine, and incessant tweeting.

So what really is going on here? Ask someone not among the Dateline faithful their thoughts on the show (go ahead, try it), and you’ll likely get a blank stare. (See?) If anything, people will associate Dateline with former correspondent Chris “Why Don’t You Have A Seat?” Hansen and his infamous “To Catch A Predator” segments, in which Zima-toting slimeballs were busted while attempting to hook up with undercover cops posing as pre-teens. (Hansen is no longer with NBC, and the “Predator” series hasn’t run since 2007.) At best, Dateline would seem to be inessential filler TV; at worst, exploitative garbage.

But that’s not the Dateline I’m talking about. Nor is the Dateline I’m talking about the kind that breathlessly updates viewers on whatever high-profile case is currently splashed across CVS checkout lanes. (Casey Anthony, Amanda Knox, etc.) No, the Dateline I’ve found myself drawn to over the last year or so is the kind that plumbs the depths of stories that rarely make headlines outside the cities they take place in. It’s the kind that features stories of run-of-the-mill betrayal and murder—stories that, while certainly tragic, are ultimately so banal and ordinary that they wouldn’t qualify for second-tier episodes of Law & Order: SVU. There may be lurid details and twists aplenty, but when they’re stripped to the bone, the best Dateline stories are just that: stories.

Some background: Dateline debuted in 1992, and was initially hosted by network heavyweights like Tom Brokaw, Jane Pauley, and Stone Phillips. The show leaned towards investigative journalism in its early days—a calling it would occasionally betray with ill-considered profiles or fudged facts. (In a 1992 segment titled “Waiting To Explode,” Dateline rigged the fuel tank of a Chevy pickup to detonate on impact. General Motors filed a lawsuit against NBC, and Pauley was compelled to issue a retraction on air.) Some shady methods aside (or perhaps because of those shady methods), Dateline became a hit, eventually running for five straight nights in the late ’90s. The show gained even more notoriety with Hansen’s “Predator” segments, but since then, it has mostly flown under the cultural radar, content to quietly go about its business of devoting an entire hour (sometimes two) to largely unheralded true-life crimes of lust, betrayal, murder, and (hopefully) justice.

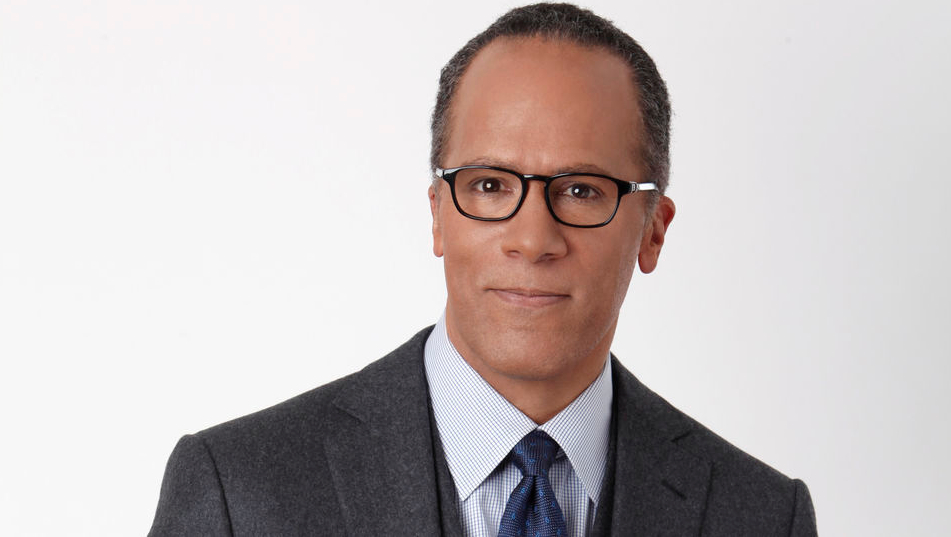

Formally speaking, Dateline does little to rock the time-tested news magazine boat. Impeccably dressed host Lester Holt—ensconced safely in the bowels of 30 Rock—begins each hour by teasing the story and tossing it to a correspondent. From there, a real-life case is presented though a series of talking head interviews, endlessly repeated still photos, the occasional family home video, and some on-location quasi-reenactments. An idyllic town and happy family are introduced. A terrible crime occurs. 911 calls are scrutinized. A suspect is grilled in a police interrogation room. Courthouse footage is shown. All throughout, the correspondent guides the story along via on-camera cutaways, usually while standing on the side of an interstate or on a dusty desert road. A cliffhanger—real or manufactured—pops up before every commercial break. A late-episode twist—again, real or manufactured—is thrown into the mix. Eerie, over-the-top music abounds.

That’s all par for the “murder of the week” course, but it’s how Dateline goes about this seemingly by-the-numbers business that hooks me—and, I suspect, others like me. First up are its personalities. While there are a number of regular correspondents on the show, the two MVPs are clearly Morrison and Mankiewicz. Morrison, with a shock of white hair and an almost-but-not-quite-winking hard-boiled delivery (ripe for an SNL parody, of course), seems almost beside himself when shaking down overzealous prosecutors or chewing through voiceover copy like, “God knows there were accusations. Oh yes, plenty of those.” Mankiewicz is a bit more subdued, gently interviewing grieving family members and sporting the occasional “You have got to be shitting me!” expression when talking to sketchy suspects. (Mankiewicz is the grandson of Citizen Kane screenwriter Herman Mankiewicz, a lineage he betrays with the occasional snippy tweet about Orson Welles.) Compare Morrison and Mankiewicz to the distinguished but rather dull on-air personalities of rival shows like 20/20—is it possible to imagine anyone but Morrison opening a story with the line, “The human heart is such a dangerous organ…”?

Correspondents aside, it’s Dateline’s solid, workmanlike approach to storytelling that sets it apart from its competitors. In other words, the thing that makes Dateline so compelling is the fact that it is largely is by-the-numbers. Take a January 3 episode titled “Killing In Cottonwood,” in which a California woman is found stabbed to death in her home. From the start, it’s clear that there’s only one legitimate suspect: the woman’s husband. But the way the show slowly doles out juicy information (Facebook chats with another woman!), zeroes in on crucial evidence (did he say “I found my wife” or “I killed my wife” in his initial 911 call?), and tosses in the occasional red herring (what’s the deal with that alternate juror?) makes the hour feel like a classically plotted “whodunnit.” In almost every significant way, Dateline is structured like any other (fictional) television procedural: a crime is exposed, suspects and supporting players are introduced, the police investigate, an arrest is made, the prosecution and defense mount their cases, someone goes to prison or walks free. The crimes themselves may not be SVU-worthy, but they’re given the full SVU treatment.

Though the show is quick to tout (and sometimes overhype) a myriad of twists and turns throughout the hour, it’s at its best when the case is cut and dry, allowing plenty of time for mulling over the details. “Killing In Cottonwood” never really presents anyone other than the husband as the potential killer (he’s eventually found guilty, though the physical evidence against him is flimsy at best), but it still gets plenty of mileage out of the little things: that 911 call, a potential mistress, painstaking interviews with the grieving family. In their own way, these standard-issue episodes of Dateline are less investigative journalism and more human-interest stories. By zooming in and devoting much of their runtimes to the particulars of a case, they become the TV equivalents of true-crime longreads.

This familiar and intimate format is also the perfect environment for a rabid online fan base—something Dateline has in spades. Viewers chime in on Twitter, answer some producer-posed questions (“Do you think Mark’s communications with his high school friend crossed the line?”), and generally armchair the investigation. Plenty of hoary Dateline tropes are discussed. Some examples:

• If a person is being interviewed in a suspiciously tight shot or in front of a nondescript backdrop, he or she is in prison.

• If someone is clearly guilty from the get-go, their defense at trial is given a mere two minutes of screen time.

• Every other episode seems to be titled “Behind Closed Doors.”

Morrison is gently mocked for his overly dramatic delivery. (Dig his hair-raising reading of “The Night Before Christmas.”) Mankiewicz’s pocket squares and baffled looks are commented on. Theories are floated that if Morrison is covering a particularly mysterious case featuring an unknown killer, he did it.

Of course, online levity and goofy contests would seem to fly in the face of the cases themselves. How can real-life crimes and tragedies be used as Friday night TV comfort food? Isn’t tweeting throughout an episode and making jokes about a killer who used to be in a band called Buck Naked And The Xhibitionists (from last season’s “A Gathering Storm”) just a wee bit tacky? Maybe, but I think it does serve a purpose. It all comes back to the type of stories Dateline does best and how it presents them. Again, these are stories that almost never make national news, stories that would normally get lost in the shuffle. A December 13 episode titled “Unstoppable” may profile the murder of a woman who once appeared in two Def Leppard videos, but the story is hardly unique (the husband did it), and the hour ultimately focuses more on an “unstoppable” best friend who sets out to crack the case. In the end, the story is less about the crime than it is about the unsung and too-easily forgotten people surrounding that crime.

So maybe in a roundabout way, Dateline works best as a sort of two-way sounding board. For those unfortunate people still dealing with the aftermath of a crime—still coming to grips with their loss, still putting the pieces back together—the show is often their only opportunity to tell their stories. Amid the din of more sensational true-crime fodder, these people use Dateline as a public venue, a chance to vent, remember, memorialize, and reach out. In turn, Dateline packages their stories in a familiar format, and the public responds. It’s a way of making sure these stories are heard, a way of making sure no one is watching alone.